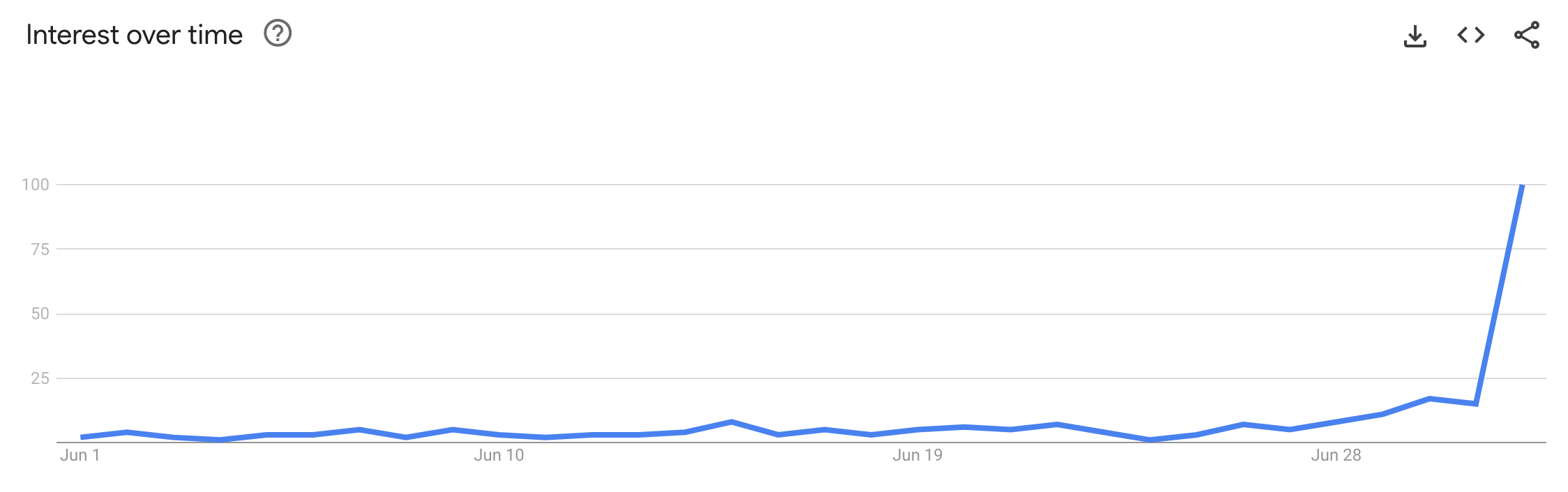

wet bulb

‘wet bulb’ trending

I was the kid with weird science kits. Chemistry sets, electronics kits, mechanical toys of all varieties. I even remember an architecture kit where I learned about cantilevers and spans by snapping little plastic I-beams together. I joke that my parents were trying to guarantee I would never know the touch of a lover, or that they were just planning way ahead to make sure I could provide a comfortable retirement for them, but the reality is that I was born a nerd and I loved it all.

I have a particularly fond memory of a weather forecasting set that I had when I was about ten. It was fairly cheap, a bent sheet metal frame with a few dials on the face and some plastic instruments on the top, the sort of thing that wouldn’t last a month outside in the elements. But I diligently measured the conditions in my room for a while, even if several of them (precipitation, wind speed) weren’t very interesting in that context.

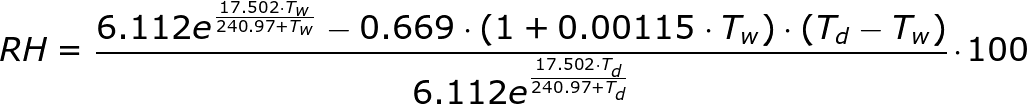

One gizmo that I do remember having some utility was a sling psychrometer. Picture two thermometers mounted in parallel on a small board, and that board mounted to rotate on a handle such that you could spin the thermometers around quickly. Nunchuks for nerds. You would take a small cloth sleeve, soak it in water, and place it on the bulb of one of the thermometers. Then you’d spin this thing for a while and read the two temperatures. The one with the wet sock would provide what’s called the wet bulb temperature; the other, maybe predictably, is the dry bulb temperature, aka good old fashioned room temperature.

The idea is that you would measure the temperature of something as water was evaporating from it, which would always be a little bit cooler than the dry one. This is why we sweat; evaporation cools things. The difference between the wet bulb and dry bulb temperatures could then be used to look up the relative humidity on a chart.1 If the air was dry, the water would evaporate faster from the wet bulb, and it would be quite a bit cooler. If it was humid, they’d be closer in temperature. This is, at a basic level, how meteorologists measure relative humidity.

This childhood memory came roaring back because the idea of wet bulb temperatures is very much in the news right now. You may have read that there is a place in Iran on the Persian Gulf where the wet bulb temperature got up to 92.7F (33.7ºC), over the weekend, which combined with air temperatures well over 100F to result in an astonishing heat index of 152F (67ºC). Now, heat index is kind of a fuzzy “feels like” number, a convenience for communicating the combined effects of heat and humidity.

Wet bulb temperature, though, is as real as it gets, and here’s why: we can’t survive very long if the wet bulb temperature gets much above about2 95F. At that point, it’s too hot for us to radiate our body heat directly into the air, and it’s too humid for our sweat to evaporate and provide any cooling. We overheat very quickly in those conditions. You might make it six hours in that; you definitely wouldn’t make it a day.

As far as my googling goes, it’s hard to get a handle on world record wet bulb temperatures, but at least according to this Wikipedia page, it got up to 36.3ºC / 97F somewhere in the UAE at some point.

We’re going to be hearing a lot more about wet bulb temperatures.

This sort of time hopping of terms coming rapidly back into vogue reminds me a bit of my experience with the idea of air quality index (AQI). Quite a few years ago, I was angry at Apple because they were suddenly cluttering their otherwise tidy Weather app with information about this new made-up measurement I’d never heard of, saying it was at levels unhealthy for certain individuals. I didn’t care! I’m not certain individuals! I just want to know if it’s going to rain on my golf game, dammit!

Raise your hand if you’ve been able to quote the AQI at any point in the last year. Things are moving quickly.